By Dr Oliver Liyou BVSc (Hons) MACVSc

Published in Australian Stock Horse Journal July-August 2005

What are wolf teeth? Wolf teeth are technically known as the first premolar teeth in horses. They usually erupt into the mouth at 5-12 months of age, but do NOT continue to grow or erupt into the mouth throughout life as do other cheek teeth. It has been estimated that approximately 70% of horses will develop wolf teeth.

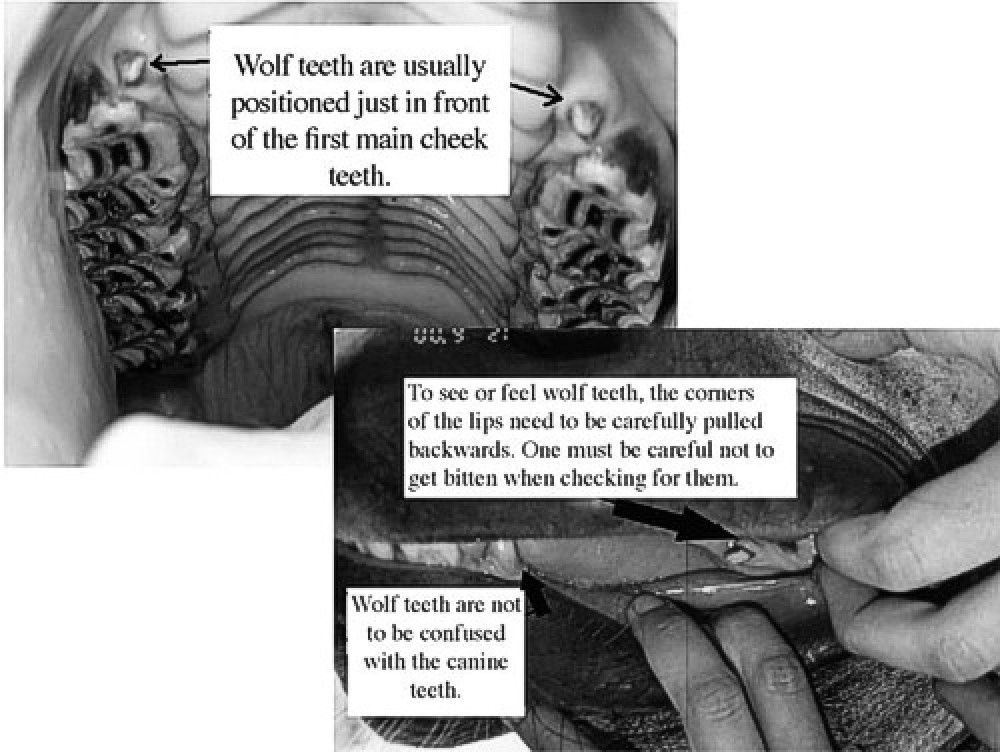

Development of wolf teeth is not sex related, so fillies appear to be equally likely to develop wolf teeth as colts or geldings. They are positioned just in front of the first cheek teeth.

Wolf teeth are usually in the maxilla (upper jaw), but can develop in the mandible (lower jaw) as well. Sometimes there may only be a wolf tooth on one side (unilateral) and not on the other (bilateral).

The majority of wolf teeth do emerge through the gums, but sometimes they do not. These are called "blind" or unerupted wolf teeth. They are usually positioned 2-3 cm in front of the first cheek tooth - much closer to where the bit is usually positioned.

What are wolf teeth used for?

They are not used for chewing, as they usually do not come into grinding contact with another tooth. Unlike the canine teeth, they are not used for fighting either.

So why are wolf teeth present?

According to fossil records, millions of years ago wolf teeth were more similar in size to the rest of the cheek teeth, and they were functional as grinding teeth. Back then, horses were small, forest dwelling brush eaters, with the cheek teeth being smaller and narrower like those of goats and sheep. Thus there were seven functional cheek teeth in each row or arcade of teeth compared to the six in todays horses.

Over thousands of years, as horses evolved into becoming plains grazers, with grasses becoming a large part of their diet, their back six cheek teeth (3 premolars and 3 molars) started to become larger, and so the first premolar cheek tooth was no longer needed in the mouth, and thus it became relatively smaller and redundant.

Why are they talked about as being a problem?

It is not entirely clear why wolf teeth were named as such, but I was once told that the word "wolf" means "bad" in one languages derivatives. And so the reputation amongst horsemen of these teeth being "bad" led to them gaining the name "wolf" teeth.

As most wolf teeth are in the upper jaw (maxilla), for most of the time the bit will usually not contact them. But when a horse throws its head etc, there is chance of the bit contacting the wolf tooth as the reins draw the bit backwards in the mouth. Wolf teeth do have nerves, and are held in the highly innervated gums and bone by the periodontal ligament. So if the bit contacts the tooth, it may induce pain, resulting in the horse tossing its head even more.

There have been many anecdotal reports of horses improving markedly in their ridden behaviour after wolf teeth have been removed.

The most dramatic case I have witnessed was a dressage horse which had a blind wolf tooth, and for the first 10 years of its life, it had not worried the horse. But when the horse went into a double bridle, the bit was now pushing on the gums overlying the tooth and caused the horse pain. This resulted in the horse actually striking at its mouth as the rider was pushing the horse up "onto the bit".

With extraction of the wolf tooth, the horse quickly resumed its normal good behaviour.

What should be done with wolf teeth?

The industry standard for wolf teeth is "Wolf teeth don't do any good, they may do some harm, so extract them all - if the horse is to be ridden or driven in a bit".

The main reason for removing them is that by getting them out of the way, we create good access so that we can properly and carefully contour the first upper and lower cheek teeth to maximise comfort with the bit.

Above right: sharp point on first cheek teeth; Above left: sharp point removed.

This procedure is commonly known as doing a bit seat. It is a misnomer, as the bit usually doesnt sit back against the first cheek teeth, but it does push the cheeks back into the first cheek teeth.

If the teeth are sharp then pain avoidance behaviours such as head tossing, lugging, rearing, pulling hard, bolting, getting tongue over the bit, head tilting, not taking one lead etc. may result.

If the teeth are sharp then pain avoidance behaviours such as head tossing, lugging, rearing, pulling hard, bolting, getting tongue over the bit, head tilting, not taking one lead etc. may result.

Thus breeding stock need not have their wolf teeth removed.

In the case of a well performing mature horse over 10 years of age, which is not likely to go into a double bridle etc, and has very good manners when bitted up, would also probably also be excused from needing to have them removed. But I still often advise to extract these properly and under sedation and local anaesthetic. By doing this, I hope to prevent the situation for the horse, if it is sold on in the future, where then an amateur "tooth rasper" may come along and smack the tooth out with a hammer and screwdriver.

How should they be extracted?

Until an operator who 'smacks' out wolf teeth with a hammer and chisel (or screwdriver) will lie down and allows me to knock out one of their teeth in a similar way, and then reassure me it doesn't result in a sudden onset of pain and long memories and fear of pain associated with anything poked into their mouths eg worm pastes etc, then I will continue to use sedation and local anaesthetic to extract wolf teeth - as I would ask my dentist to do to me.

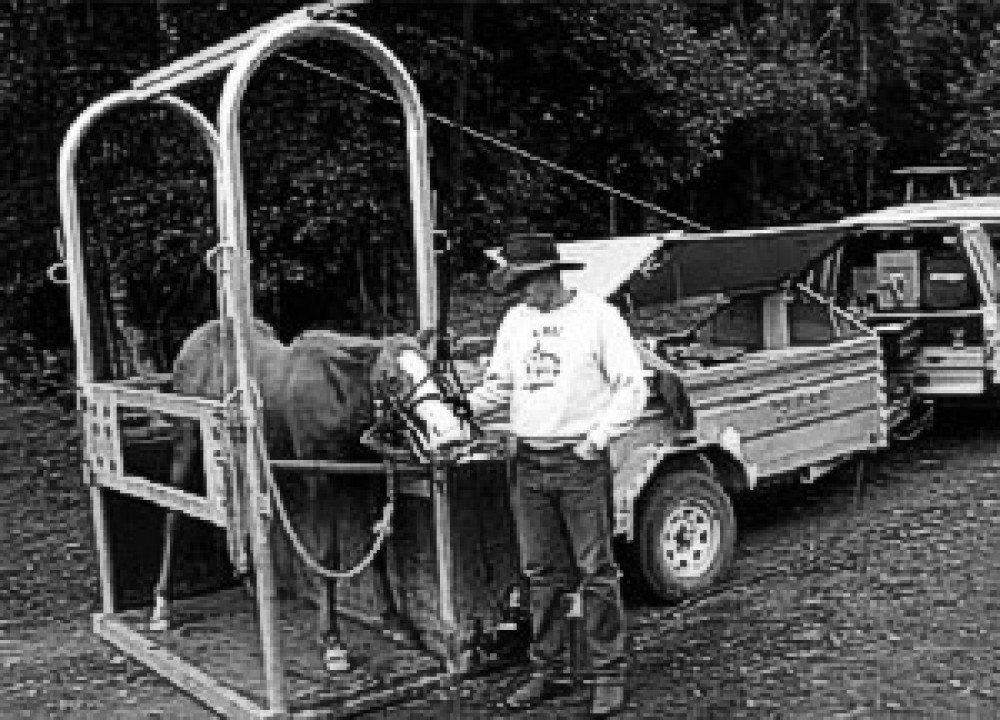

18 month old filly is sedated in the Porta Safe Stocks and the wolf teeth have been nerve blocked ready for extraction

18 month old filly is sedated in the Porta Safe Stocks and the wolf teeth have been nerve blocked ready for extraction

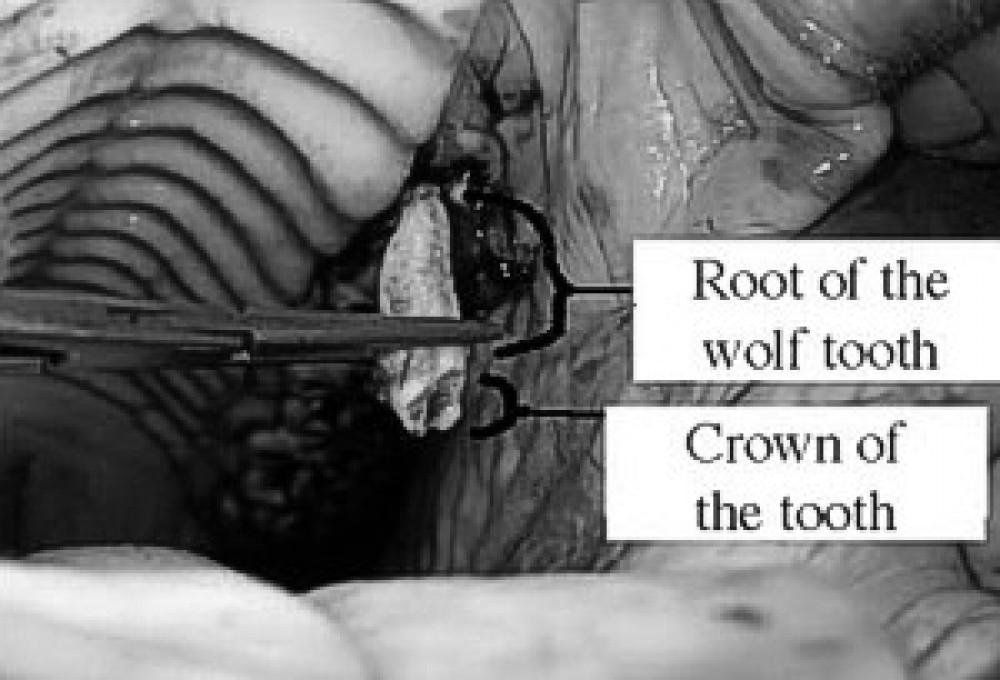

The 18mth old filly's left upper wolf tooth appears to have a crown height above gum of 6mm

The 18mth old filly's left upper wolf tooth appears to have a crown height above gum of 6mm

Upon extraction, it can be seen there was a long root attached

Upon extraction, it can be seen there was a long root attached

By smacking out the tooth with a hammer and chisel, most of the root will be left behind, fractured and with an exposed nerve. If the gum can heal over that nerve and fractured root, then all may be ok, but if it doesn't, then the tooth root may become infected as it dies and remain as a source of pain.

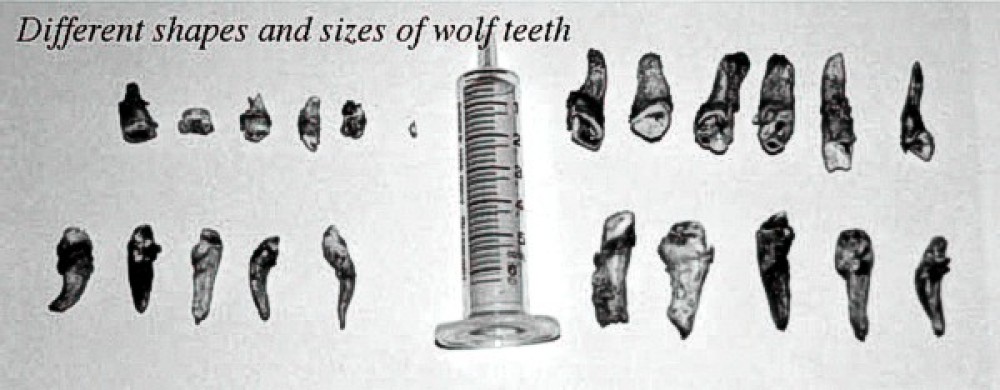

Above: Wolf teeth come in a wide variety of shapes and sizes, so one should never assume how shallow or deep a wolf tooth root will go!

Many years ago, as with tying down and castration of colts without any anaesthetic, knocking out of wolf teeth was acceptable as the ONLY way possible. But as we learn about how horses vividly remember painful events for such a long time, and base their trust values on events such as these, good horsemen and women are realising the value in performing painful procedures on horses under sedation and/or local anaesthetic. Sometimes, general anaesthetic is indicated.

Thus no bad memories are formed and trust levels can remain high.

The correct method of wolf tooth removal is by using sharp, clean elevator to cut the gum, and stretch the surrounding periodontal ligament to loosen the tooth. As wolf teeth come in many different shapes and sizes, this procedure may only take a couple of minutes, or it may take 10-20 minutes.

Patience is the key and one must be gentle to ensure the periodontal ligament is being stretched and fatigued, leading to it being loose enough to remove. Once loosened, then forceps can be used to grasp and remove the tooth. Obviously the mouth needs to have been cleaned and flushed to make the dental procedure as clean as possible.

Tetanus

As horses are highly susceptible to the toxins from the tetanus bacteria, clostridium tetani, it is imperative in a horse which is undergoing wolf tooth extraction, that the horse is sufficiently protected by means of vaccination.

It is not good enough that a horse had only one vaccine in its life, usually when it was gelded in the case of males. This situation will mean the horse is not protected and the effort and money spent on the first vaccine has been wasted. Suffcient protection requires a second booster vaccine administered 4-6 weeks after the first vaccine, and then a booster every 2-4 years.

The disease known as tetanus is usually fatal in horses, and mares seem to be over represented, as they are not castrated! The wounds in which the tetanus bacteria thrive are usually well hidden, small puncture wounds where there is no oxygen (anaerobic conditions). Thus mouth cuts and wounds eg after wolf tooth removal are the perfect environment for tetanus bacteria to grow.

Foot puncture wounds and foot abscesses, wire punctures, splinters are also ideal wounds for tetanus to thrive.

We continue to see cases of horses dying from tetanus every year. So hopefully through better education of horse owners, this will become a rare disease. The vaccine costs around ten dollars per dose, and yet is highly protective.