By Dr Oliver Liyou BVSc (Hons) MACVSc

Published in Australian Stock Horse Journal March-April and May-June 2005

In this article, I will attempt to explain a condition which many horse owners have seen, but few understand it well. This is due mainly to the fact that there remain a lot of questions regarding the condition. These questions require sound scientific studies in order to be properly and accurately answered.

Parrot mouth has several other names and these include: brachygnathism, overshot maxilla, buck tooth, undershot jaw or overbite.

The definition of a parrot mouth is when the top incisor teeth's front edge is further forward that that of the lower teeth. Obviously there are all different degrees of parrot mouth — minor through to severe. In minor cases, the upper and lower incisors still meet, but are not perfectly aligned, but in severe cases, the two do not meet at all.

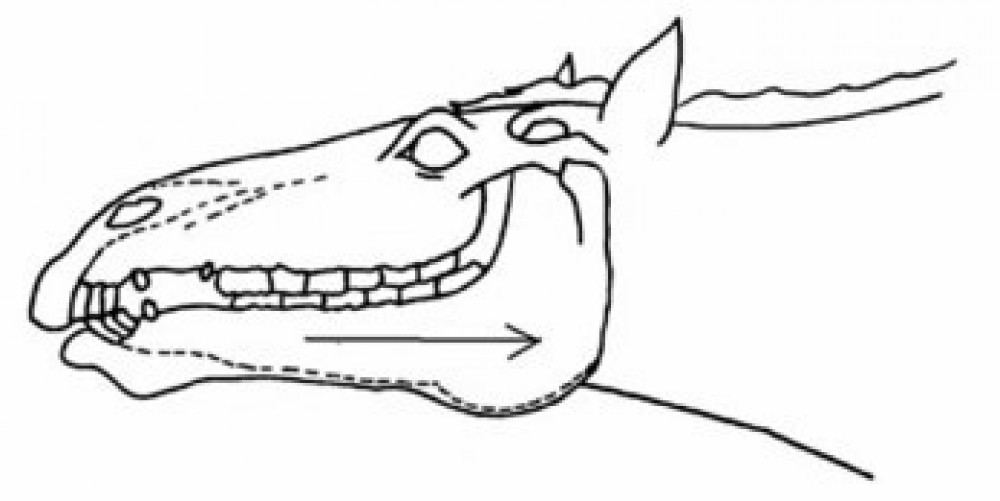

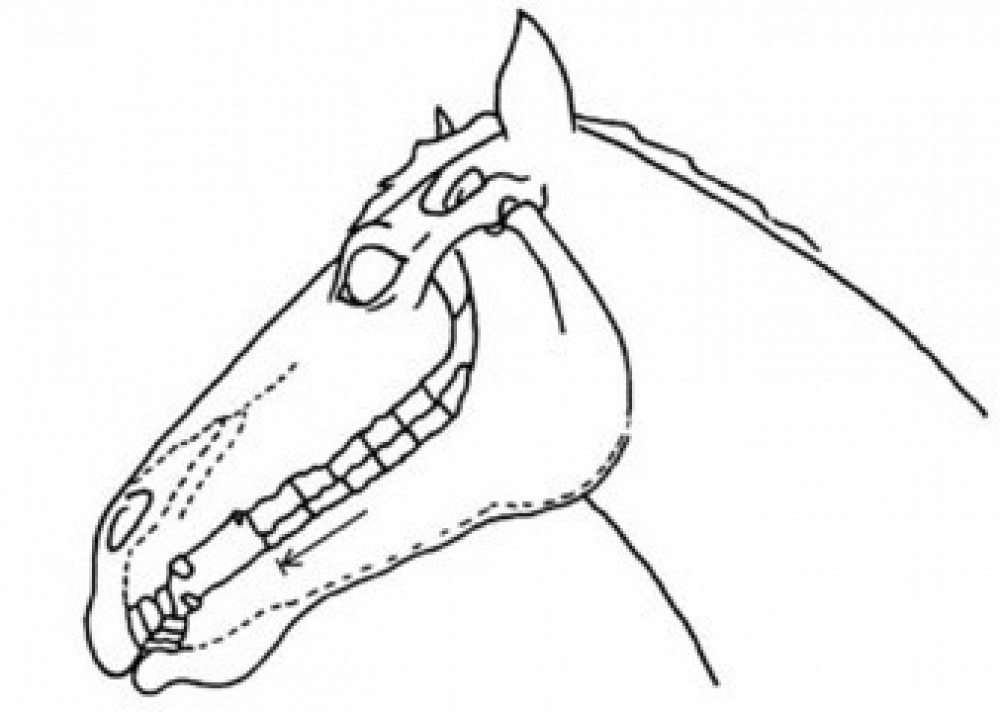

It is important that the horse's incisor bite be checked with the head in the normal resting position and not raised up high. Raising the head high, or extending the poll joint, will cause the lower jaw (mandible) to slide backwards (caudally) slightly (approx 3- 10 mm). Conversely, when the head is lowered and the poll flexes, the lower jaw (mandible) slides forward.

This backward and forward sliding of the jaw when the head is raised and lowered is known as Rostro-Caudal Movement (RCM). It is a normal process which is required for normal chewing and comfort to the horse when ridden. So even though most of the jaw movement when eating is from side to side (lateral movement), there is also a small amount of backwards and forwards movement of the lower jaw (RCM).

Parrot mouth may occur in any breed of horse, and it has a reported incidence rate of 2-5 %. This is fairly significant when you think that 2-5 out of every 100 horses have parrot mouth to some degree.

Parrot mouth in a horse is often not present as a newborn foal, but becomes apparent when the horse is over 1-6 months old.

The cause of parrot mouth is often not fully clear.

Several causes are possible including genetics, trauma and illness as a foal near a period of rapid growth.

The condition can result from the top jaw (maxilla) developing too long, or the bottom jaw (mandible) developing too short. Usually it is the lower jaw that is too short. But anything which interferes with the match up of the top and bottom jaws can cause a horse to be parrot mouthed.

As far as genetics go, parrot mouth is NOT directly heritable. That is, we rarely see an individual sire or a mare throwing an abnormally high number of parrot mouthed foals. The most common cause of it is when a mare is bred to a stallion of very different head type. Surprisingly, these two stud animals often have normal teeth structure, yet when they are bred, the mismatch is so great that a parrot mouth offspring is produced.

The commonest example of the mismatch is when a stocky and short, wide headed stallion is bred to a lean long headed mare. Thus a breeder needs to be careful and considerate even of head type when planning to breed a superior foal.

It is important to remember that malocclusions in horse's teeth (when they are not in the correct positioning and alignment etc) is poorly understood when it comes to how heritable it is, and is often a very complex mismatch of many genes. Thus having a badly conformed mouth in your animal may present a risk in breeding, but certainly doesn't mean that animal will throw offspring with a similar condition.

So the breeder needs to consider questions such as:

- how bad the condition is

- whether the dam or sire has produced other similarly affected offspring

- whether the affected animal has thrown foals with a similar problem.

These negatives then need to be weighed up against the positive desirable traits of that animal.

Whilst it is ideal to not breed any animals with faults, if we all did this, then there would be no foals next year! So with the parrot mouth condition, one strategy could be to not re-mate a mare to a particular stallion if a parrot mouthed foal is produced by that mating.

In improving a breed, we should always aim to breed animals with similar positives, but different negatives.

It always amazes me to watch and see how even severely parrot mouthed horses can eat short grass and do amazingly well in body condition. I know one good horseman who actually believes that parrot mouth horses are usually very athletic! You may not realise but the great galloper Kingston Town had a parrot mouth.

So why is parrot mouth undesirable?

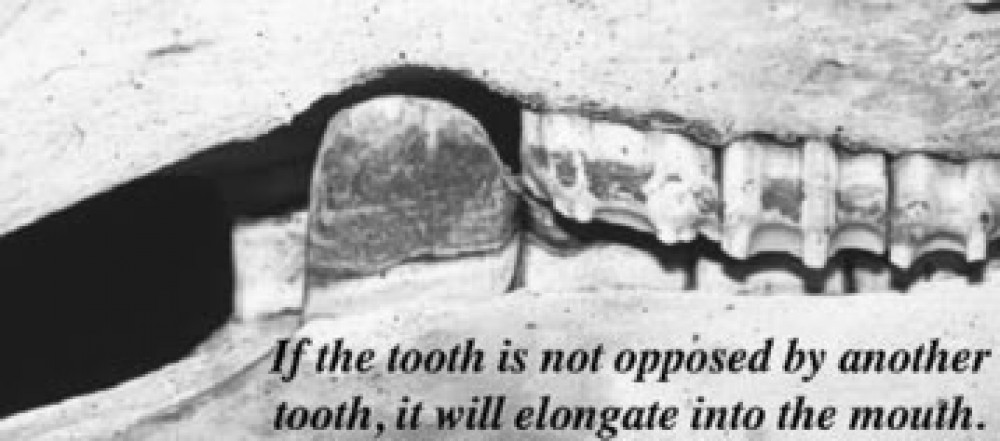

The real problems with being parrot mouthed are due to the fact that horses' teeth are hypsodont teeth — that means that they have long crowns up in the bone and continue to erupt or move into the mouth throughout life — up to a point where there is no more tooth left to erupt into the mouth. If they are not opposing another tooth, they continue to erupt into the mouth to a point where they are a problem and dig into the opposite jaw etc.

Horses' teeth do not grow indefinitely like rabbits' teeth, but for some time they continue to erupt into the mouth — with the purpose being to replace the tooth which is worn away during the chewing process. Because a paddock grazing horse may on average chew approximately 20 million times per year, the highly repeated grinding of tooth on tooth, or tooth onto fibrous feed material will lead to wearing away of the tooth. Thus new tooth needs to erupt into the mouth to replace the tooth which has been worn away. This tooth eruption process usually continues up until the horse is 15- 20 years of age — but sometimes more and sometimes less.

It is this fact that there is only so much tooth available to be used in a horse's life, that the teeth — if normal height and angle, should NOT have their grinding surfaces ground smooth by an equine dental practitioner. Nature provided the horse with teeth made from three different substances — enamel, dentin and cementum — which all wear away at different rates. This produces a rough grinding surface which will effectively crush feed ready for digestion. Smoothing of the tooth's grinding surface will often render a horse in pain and unable to chew its food properly for days to weeks — a very disturbing situation — especially for the horse!

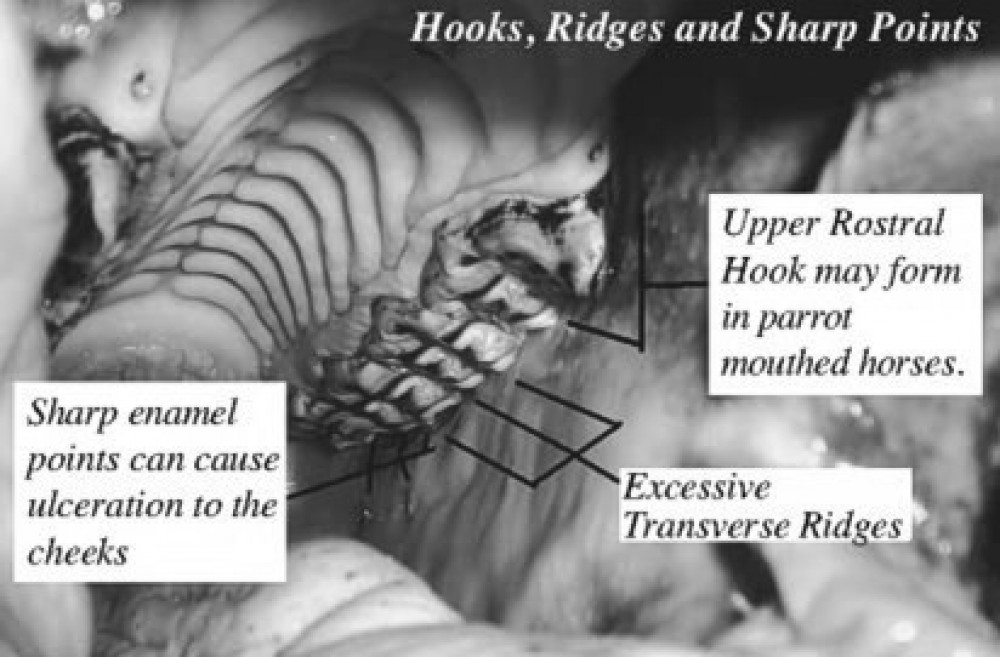

Unless the tooth is abnormally high or the angle is wrong, the smoothing of a tooth's grinding surface will reduce the life span of that tooth by at least 50 % if this procedure is repeated each year. What I am saying is not to be confused with the fact that the waste tooth eg sharp enamel points, tall teeth, hooks, waves, ramps, excessive transverse ridges etc, should not be removed or reduced at a dental visit.

So what happens if opposing teeth don't line up properly?

The eruption process of teeth works fine if the teeth all line up even and oppose one another. But if they are not matched, then the tooth which is not opposed will continue to erupt into the mouth and become longer and longer.

As the elongating tooth or teeth become more prominent, they may cause the tooth to be moved or forced out of its normal position and they also may restrict the whole jaw's normal RCM (rostro-caudal movement) whilst eating or when ridden.

Some examples of the secondary effects of parrot mouth are elongated lower incisors — where the lowers may cause ulceration of the roof of the mouth's (palate) lining (mucosa). This obviously can be painful to the horse and restrict its ability to graze properly.

Parrot mouth horses often, but don't always, have problems back in the cheek teeth occurring as a result of the incisor overbite.

The three most common secondary problems are hooks, excessive transverse ridges (ETR's) and sharp enamel points.

These conditions may all cause major problems to the horse — whilst eating and when ridden — both in the short term and the long term.

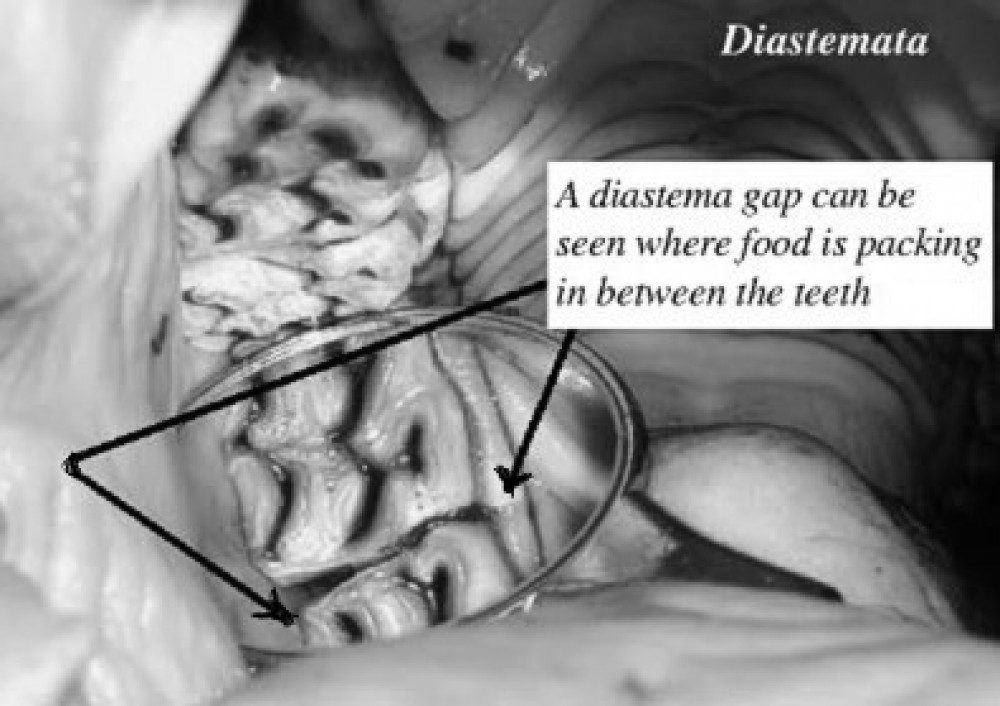

As you can imagine, with 20 million chews per year, a hook on the upper first cheek tooth could result in that tooth being pushed forward away from the tooth behind it. Thus an abnormal gap in between the teeth would result, and feed becomes trapped in that gap, leading to rotting of the feed and severe gum disease (periodontal disease).

Periodontal disease is very common in horses, and needs to be detected early. If left untreated, it becomes irreversible, and often leads to premature loss of that tooth, and/or possible tooth root abscess formation. As those of you who have had meat stuck between your teeth for a few days, periodontal disease produces bad breath (halitosis) and can be quite painful. It may cause a horse to chew slowly, pack feed inside its cheeks (quid), drool saliva and tilt its head when eating etc.

When being ridden the hooks and ridges restrict the free gliding movement of the jaw (RCM) during flexion and other changes in head position. Thus these affected horses may be not as light in the mouth as they should be during collection, or they may work behind the bit, or they may have a bad head toss at transitions.

The hooks, ridges and sharp enamel points can result in wide and varied behavioural expression — from nothing at all in some very tolerant and well trained horses, through to lugging, getting the tongue over the bit, chewing the bit, head tossing, bolting, rearing and even bucking in other horses.

As with people there is a massive variation amongst horses in tolerance and behavioural response to problems and disease in the mouth.

Treatments for Parrot Mouth

For mild cases, special performance floating by a qualified, knowledgeable equine dental technician or vet will go a long way to correcting the problem. It may take several treatments but it can be done.

Mild cases include those where the incisor teeth (front nippers) are meeting, but not in 100% contact.

The floating must be certain to address the associated overgrowths of teeth which arise and encourage the backwards displacement of the Mandible (jaw). These overgrowths include lipping of the incisors, hooks on the cheek teeth and excessive transverse ridges on the cheek teeth. Obviously the sharp enamel points must also be addressed.

For more severe cases, orthodontic techniques are often required. But this should not discourage the owner from requesting high quality dentistry to be performed, as major improvements are possible as the horse is growing.

It must be noted that these parrot mouthed horses may well be the result of genetic "mismatching" or heritable disorders, and so breeding from them must be considered carefully.

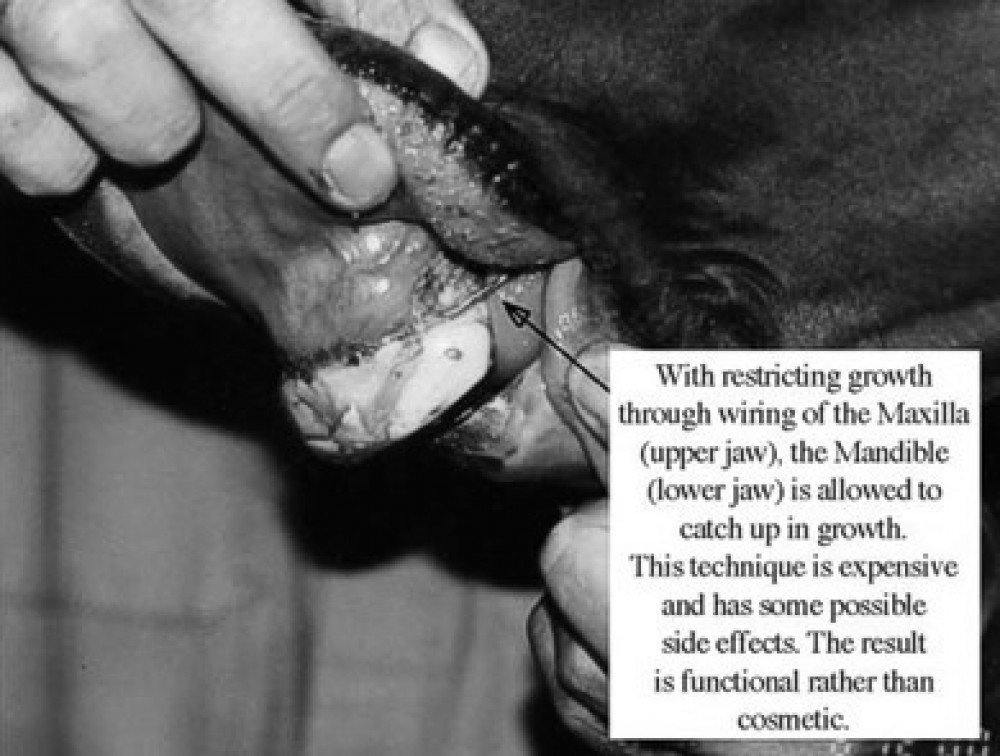

Orthodontic techniques are those which include wiring and/or plating the mouth. These techniques are not simple and so need to be performed by a competent and experienced veterinary surgeon.

The results of these orthodontic techniques are more functional than cosmetic, and there are possible side effects. The wiring requires many general anaesthetics as the jaw grows, so the orthodontic wiring programme becomes quite expensive and will need to continue for months to years. It needs to be commenced when the foals are young, but the foal needs to be able to eat creep feeds such as pellets and chaff.

It is not surprising that it is uncommon to see badly parrot mouthed horses surviving into their late teens. Without rigid dental care, they struggle to cope in the paddock — year in year out.

For an equine veterinarian in your area who may be able to assist you with your parrot mouthed foal, contact the Australian Equine Veterinary Association (AEVA) office on 02 9411 5342. The AEVA maintains a list of over 100 equine vets, from all states in Australia, who have a special interest in equine dentistry. This list is growing all the time, as we all recognise the importance of good dental care, and regain the enthusiasm and interest in dentistry that was enjoyed before the motor car arrived — when horses reigned supreme!